Now, as the US dollar rises against almost all currencies, the scenarios of economies of many countries falling into depression are multiplying, due to inflation growth, world trade decline, capital flight, growing debt imbalances, etc.

No country in the world is immune to possible "negative" pressure on its national currency. If every significant weakening of a national currency were destructive for the national or global finances and economy, there would be no global development at all. In reality, the governments of "successful" countries are always trying to take advantage of the unfolding situation – not through countering the currency pressure but using exchange rate fluctuations to promote business activity and maintain the living standards.

Exchange rate influences. Let us analyse the impact of exchange rate dynamics on certain components of the economic environment of some developed countries in the last decades of the past century. That period is quite interesting and instructive for planning and implementation of economic encouragement measures and tools. It is characterised by flourishing monetarism, which became one of the factors of the global economic acceleration, creation of a single monetary system of the countries of Europe (where each country had its own currency until the end of the 1990s that fluctuated "freely" against the dollar, yen, etc.) through the liberalisation of global flows of goods and capital.

Meanwhile, due to the growing international competition in the conditions of free exchange rate fluctuations, countries had to quickly adapt to changes in the global environment and emerging currency or monetary imbalances. During this period the greatest strengthening of the dollar took place in early 1980s, when the European Monetary System (EMS) was being formed, and the policy of promotion of the US economy ("Reaganomics") was actively implemented. Another crisis in the European currency markets took place in the early 1990s, when the Maastricht Agreements were concluded and Great Britain left the EMS.

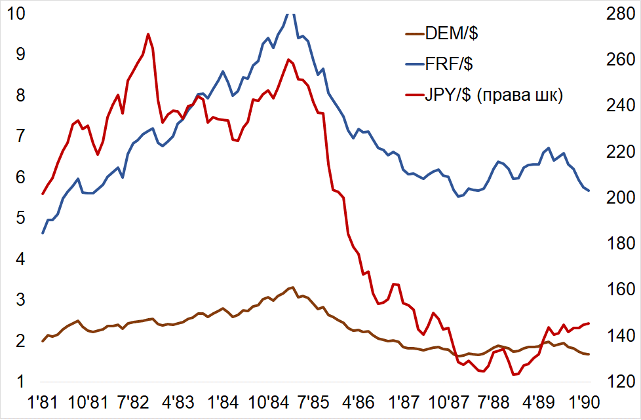

The main currencies were cheapening and appreciating within a short period of time. Say, at the beginning of 1981 one USD cost about 200 yen; at the beginning of 1985, the exchange rate rose to 260 yen per USD (strong devaluation), and in 1989 it fell to 120-140 yen per USD (strong revaluation). Fluctuations of the other key currencies were also significant. The value of the German mark in the same period rose from 2 to 3.3, then fell to 1.7; the relevant indicators of the French franc were 4.6, 10 and 5.8 (diagram "Exchange rates of major currencies").

In the second half of the 20th century, the Japanese economy was among the most dynamic in the world. By the turn of the century, the country that came out of World War II defeated and devastated took the second position in the world economic rating, thanks to the "Japanese miracle". Japan's success was largely determined by the success of its heavy industry, mechanical engineering, electronics and, above all, the car-making industry, which became the country's "icon". Of course, Japan's export-oriented industry in general and automobile production in particular had to respond to rapid changes in exchange rates.

Exchange rates of major currencies, units of national currency for $1

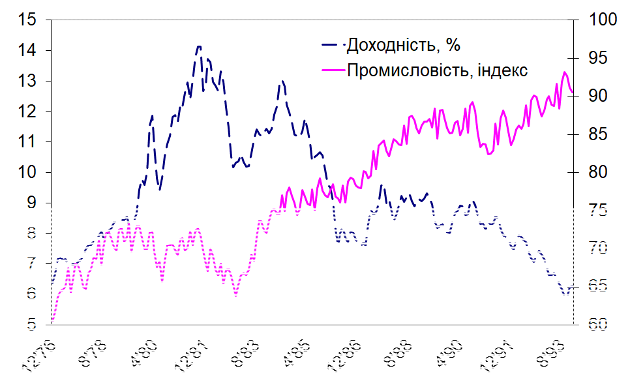

Strong devaluation of the yen (mark, franc, etc.) in the first half of the 1980s was caused not so much by internal problems (the Japanese economy developed at a steadily high rate) but by the strengthening of the dollar as a result of the monetary and fiscal expansion of the United States - the "Reaganomics" policy. The yield on US government bonds was maintained at a much higher rate (Chart "Yield on long-term bonds..."), which ensured the inflow of capital. At the same time, this reorientation of capital had "negative" effects. In particular, the dynamics of industrial production somewhat slowed down, as the values on the money markets rose, and the trade balance deteriorated.

Yield on long-term bonds (left scale) and US industry index (right scale)

For Japan, high (and growing) values of the nominal exchange rate (with low inflation) meant a real undervaluation of the yen, which provided additional external advantages, and in the first half of 1980s a significant increase in exports took place, including to the US markets, which required additional regulation (restriction) of exports to prevent excessive trade surpluses and deficits.

Growth of economic and financial imbalances even prompted the finance ministers of the leading countries of the world to sign a joint agreement ("Plaza") in September 1985, which provided for a significant weakening of the dollar to the other major currencies, leading to a rapid strengthening of the yen (chart "Exchange rates of major currencies"). At the same time, the rapid revaluation of the yen and restrictions on exports slowed down the growth rate of the Japanese industry and the economy in general.

Impact on production. What did sharp currency fluctuations mean for Japan's automotive exports to the US, where Japanese cars were in steady demand? The devaluation of the yen (in early 1980s) made Japanese cars significantly cheaper (in dollar terms) in the US markets. US consumers switched to Japanese makes (the price difference could reach 10-20% even with customs). At the same time, Japanese exporters obtained extra alternative benefits:

- A) to raise the dollar price of their cars to the level of US ones, receiving significant income in yen on each unit sold without significant changes in sales volumes;

- B) to take advantage of the dollar price drop (with the income in yen for each car sold unchanged), to boost sales or the market share of Japanese cars in the US market; the income will rise due to the increase in sales.

Of course, a third option is possible, with a slight decrease in the dollar price, leading to an increase in the market share, so that total revenues also increase. In practice, a combination of these tactics was used, dependent on additional export conditions.

Thus, in the first half of the 1980s, Japanese car manufacturers preferred to maintain the dollar price (receiving significant income in yen for each unit). The other alternative was politically complicated, as in 1981, Japan agreed to introduce the so-called "voluntary export restrictions" (the country independently limited exports to the USA (which effectively meant the introduction of quotas), because at that time the US society was concerned about the "conquest" of the US car and electronics markets by Japan).

However, this approach brought benefits later. With additional revenues, Japanese car makers focused on the quality of their products, and benefited from higher prices of new products with a higher added value.

Redistribution of market shares could reverse, when the yen began to grow (1985-1989). Then, the price of Japanese cars rose due to the revaluation of the yen. However, US manufacturers ignored the possibility of expanding their share in the domestic market (maintaining stable prices, while the price of Japanese products was rising). Instead, the price of US cars rose almost equally with the Japanese (due to the revaluation of the yen). Hence, Japanese cars did not disappear from the US market.

Moreover, since in previous years Japanese manufacturers made efforts to raise the quality of their products, such measures contributed to strengthening the Japanese presence in the US markets. The quality of Japanese models continued to be higher than of US makes of a similar class, and with that, export expansion continued (at a lower pace though).

That is, under balanced approaches, competitive enterprises and sectors of the economy may receive extra benefits even in worsening foreign trade conditions or currency imbalances (not trying to break restraining macroeconomic trends).

Containment of devaluation pressure. In most cases, the national economic environment is quite sensitive to the dynamics of national currencies (which is often manifested through the import of inflation, trade imbalances, capital flight). Devaluation trends in emerging countries are especially undesirable. In such cases, governments (central banks) try to restrain the pressure on national currencies with proven measures - interventions and interest rate increases. Possibilities for interventions are usually limited, including as a result of the provoked erosion of the national currency reserves. Thus, the weakening of the national currency often leads to negative "side effects":

- higher interest rates,

- stronger inflationary pressure,

- reduction of production and revenues for the country.

A significant disadvantage of higher interest rates is presented by the associated suppression of the real sector, which can worsen the economic environment even more, and with it, bring new interventions, interest rate increases, inflationary risks, etc.

Surprisingly, macroeconomic stabilisation can take place in case of "yielding" to devaluation pressure. Of course, only developed countries with a strong financial sector can afford it. This was observed in early 1990s, when some European countries refused to support the mechanism of joint fluctuation of currencies, because such support led to macroeconomic imbalances (growth of interest rates, inflation, pressure on the real sector).

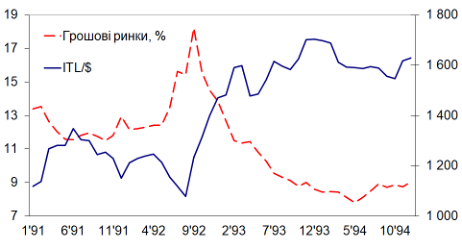

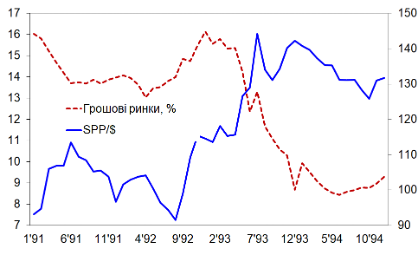

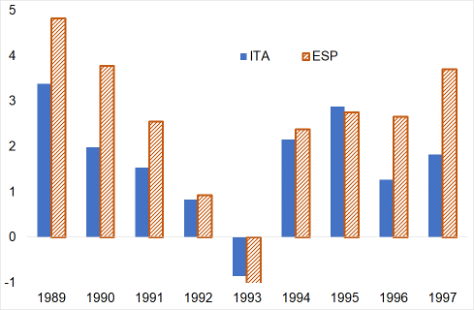

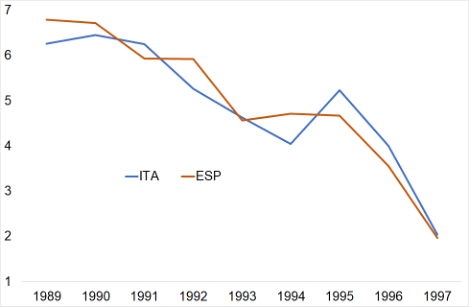

The developments in the European foreign exchange and money markets in 1992-94 showed that in presence of capacious domestic markets, a good option may be presented by devaluation of the national currency, accompanied with lower interest rates (diagram "Interest rates of money markets..."), which is accepted by business and allows economic growth through better lending conditions and lower inflation (GDP Growth and Inflation chart), in this way raising the competitiveness in foreign markets. At the same time, the objective of removing the negative pressure on the national currency is achieved.

Interest rates of the money markets (left scale) and exchange rate of the national currency (right scale)

Italy

Spain

Therefore, the weakening of "support" for the national currencies in some developed European countries in early 1990s brought:

- lower interest rates,

- containment of inflationary pressure,

- growth of production and revenues for the country,

i.e., had consequences opposite to those often seen in emerging countries. Moreover, said mitigation of the devaluation pressure only highlights sophistication of the tools, which should be based on a balanced macroeconomic policy.

GDP growth and inflation, % to the previous year

GDP

inflation

Which way will Ukraine choose? The current development of Ukraine has no historical precedents. Therefore, the search for appropriate measures and tools of economic recovery and encouragement, including mitigation of currency imbalances and devaluation shocks, remains relevant. Let us consider several "currency" features.

Since the Ukrainian business and households were, are and will long stay dollar-oriented, transition to a free exchange rate is out of the agenda now. At the same time, in the conditions of persistent devaluation pressure on the national currency, interventions remain effective and may be fully justified. However, the question remains how long those interventions may last, if the devaluation pressure persists, along with depletion of the reserves. Specificity of the current moment for Ukraine is in the strong long-term support of international partners, which ensures the steady replenishment of the national currency reserves.

By and large, the use of significant reserves to maintain the exchange rate (with higher interest rates) does not seem a good option. The tasks of creating an environment favourable for the domestic business under an open economy and withstanding competitive pressure on domestic and foreign markets (after joining the common European market) are becoming even more urgent for Ukraine’s recovery.

Only in the presence of competitive enterprises and industries, Ukraine can take advantage of any exchange rate dynamics of the hryvnia, as was demonstrated by Japanese cars conquering the US market, even if in the short run, exchange rate changes may look unfavourable, as they seemed in Italy and Spain (see above).

The overall lines of Ukraine’s recovery should pursue two "macro goals": formation of a security structure of the national economy, and full integration of the national economy in the European economic environment. If appropriate mechanisms are provided for in the future "Marshall Plan" for Ukraine, one may hope for success.

So far, the situation with support for the penetration of the Ukrainian business to competitive markets is extremely uncertain. Even less attractive is the situation with foreign investments, indispensable for success even in the medium term. However, significant progress in improving the economic and investment situation in Ukraine (even in the conditions of the war), given the high risks that negatively affect investment decisions, may be secured by:

- Conclusion by Ukraine of investment insurance contracts (of investment guarantees) in the largest donor countries (the USA, the EU, Japan), which can be paid for out of the partner countries’ assistance;

- Establishment of a fund (with US or British financial institutions) to insure political and military risks for foreign investors, as well as to support domestic exporters and investors in international markets.

Meanwhile, the proximity of the enemy puts militarisation of the economy and significant strengthening of the security sector on the agenda. The engine of economic development at this time should be presented by the defence industry, focused on production (in cooperation with foreign partner companies) of the widest possible range of weapons. Such a military-industrial potential may be achieved only with support of partner countries, which will ensure stable competitive demand, and Ukraine will find a competitive niche withstanding external fluctuations.

See the full article in Ukrainian at: https://razumkov.org.ua/statti/yak-vykorystaty-kursovu-dynamiku