Over the past three years, Ukraine has faced two deep socio-economic crises. The "sources" of these crises are different: the crisis of 2020 was caused by the global coronavirus pandemic, and 2022 became tragic for the country due to the Russian aggression. At the same time, a certain similarity in Ukrainians' readiness and perception of crisis processes indicates the expediency of a comparative analysis of crisis effects and results.

We will briefly examine Ukraine’s socio-economic losses of 2022 in the context of the crisis of 2020 (but not the previous, relatively "calm" year of 2021).

From crisis to crisis. Although the global nature of the two crises — the coronavirus one, and the one caused by the war in Ukraine — is different, their visual symptoms have common features. The normality of the day is half-empty streets, shops and pharmacies that work under special regimes (mask requirements or electricity supply), restrictions on people’s stay out of homes or work, transport disruptions, buying foodstuffs for several days or even on stock, shock jumps in the prices of prime necessities, fiscal and currency imbalances. At the same time, there are similar good signs — easing of administrative, tax and regulatory pressure, state support (albeit limited) for households and businesses.

It is hard to say for sure the symptoms of which crisis we are talking about. And this concerns not only Ukraine.

The first thing that struck the eye during the crises was the total unpreparedness of humanity, even developed Europe, for a quick coordinated response to threats that were initially perceived as local. As a result, there were attempts to use coronavirus diplomacy, instead of real vaccination, or careful countering the aggressor, as if not to anger it.

The inconsistency and controversy of interstate actions became especially shocking. Even when the coronavirus wave became global, the search for and production of drugs was not internationalised. At the same time, it was accompanied by excessive bans and social control not only to comply with quarantine requirements but also (in many countries) to restrict civil rights and freedoms. While governments mobilised resources for healthcare and medical treatment during the coronavirus attack, trade and transport collapsed, work was barred, and the effectiveness of crisis response measures left societies unprotected.

The inconsistency in the fight against the coronavirus can still be explained by its unexpected unprecedented scale, although in the last decades, epidemics of various kinds have occurred almost every year (albeit on a smaller scale). No one expected a war in Europe either, and European governments were lulled by the reliability of NATO (as if a guarantor of peace by itself). Poor coordination of positions of the EU and NATO member states (where one country can block an extremely necessary decision, not particularly worried about the global consequences and risks) could even help the aggressor. Of course, Europe's lethargy could not but be influenced by Ukraine's underestimation (or even neglect) of the risks of an invasion and a full-scale war.

The war had a differentiated impact on societies: countries were affected by it to varying degrees and reacted differently. On top of Ukraine of course, whose losses are unprecedented, many countries lost access to resources due to high import costs, although this was not a shock. At the same time, a number of countries seemingly did or could win (energy exporters), or received additional gains to make up for the missed benefits (cheap energy resources), which brought risks to strategic partnership (Hungary's demands to the EU).

Psychological losses were added to economic ones and multiplied them. Thus, characteristic features of human behaviour during the coronavirus included the tendency to stay at home, remote work, forced compliance with travel restrictions. The war caused displacement of huge masses of people, powerful waves of migrants that swept across Europe, causing "fatigue" in many countries.

The time factor is also important. Indeed, the coronavirus tsunami hit everyone almost at the same time, all countries suffered losses, all the usual economic mechanisms were destroyed — practically no country was able to protect itself. However, the main risks had a time-limited dimension, as evidenced by the football World Cup, where no one out of the tens of thousands of fans in the stadiums wore a mask. The war in Ukraine does not have a time limit yet. Although there are reasons to expect a victorious advance of the Ukrainian army, the reality does not give us the right to calm down. Therefore, it is important to pay due regard to the mistakes and complications that arose in previous crisis periods, which will give hope for their timely prevention, and with that, transformation of understandable risks into opportunities.

Macroeconomic comparison. Of course, Ukraine's losses in 2022 are unmatched. At the same time, regarding the economy, it is not surprising that the dynamics of certain important macro indicators for Ukraine had features similar to the previous crisis year — 2020, which may be an important warning in the following crisis periods (which, as evidenced by the global development of the last two decades, will come even more often). The pandemic and the war developed almost "in parallel", with an interval of 2 years (they began at the end of February and the beginning of March).

Since the GDP fall in 2022 turns out to be much deeper than during the pandemic (table "Real GDP growth"), one could expect a "commensurate" deterioration of other macroeconomic inputs. However, the situation is not so certain.

Real GDP growth

|

I'20 |

II'20 |

III'20 |

IV'20 |

Q1'22 |

Q2'22 |

Q3'22 |

|

|

% to the same quarter of the previous year |

-1.2 |

-11.2 |

-3.5 |

-0.5 |

-15.1 |

-37.2 |

-30.8 |

|

% to the previous quarter (adjusted for seasonal factor) |

-1.2 |

-8.5 |

8.5 |

0.8 |

-19.3 |

-19.1 |

9.0 |

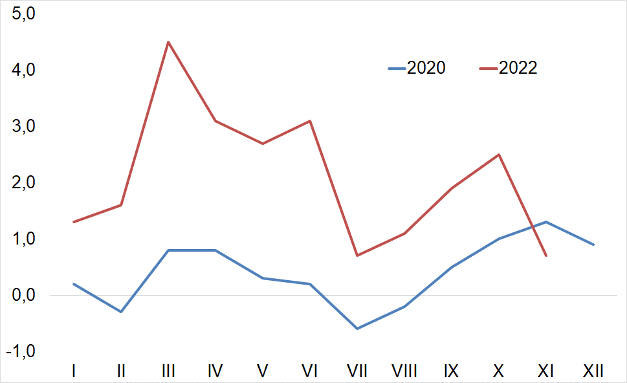

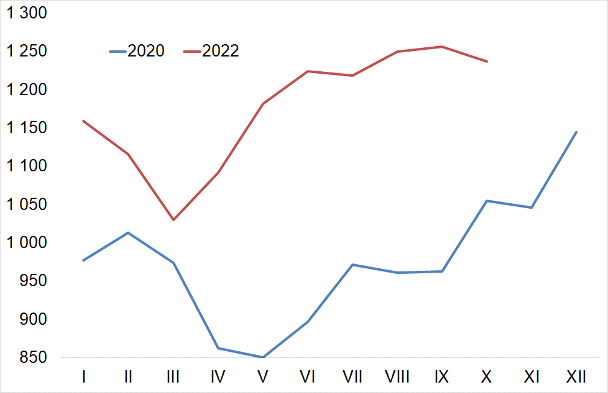

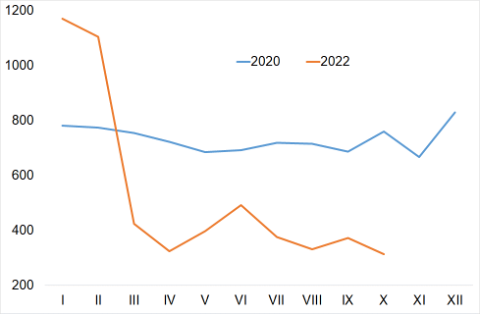

Inflation. Characteristic of economic dynamics in both 2020 and 2022 was a distinct increase in inflation, primarily as a result of growing foodstuff prices. Moreover, the inflationary spike in March-April (in both cases) was associated with excessive demand for consumer goods and essentials (including because households made stocks of such goods in conditions of high uncertainty) (diagram "Consumer price rise")

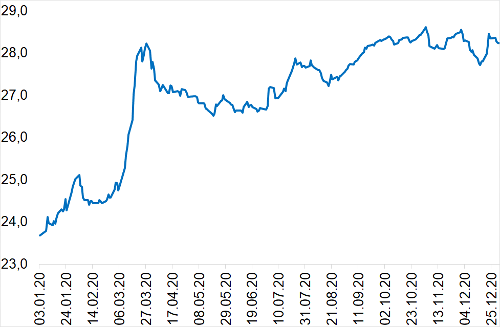

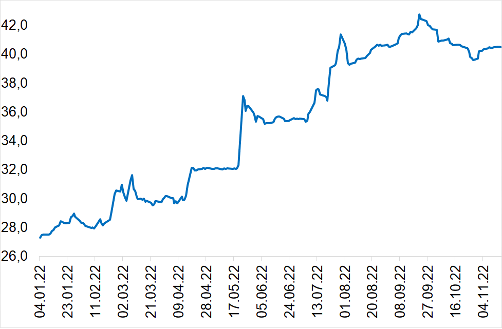

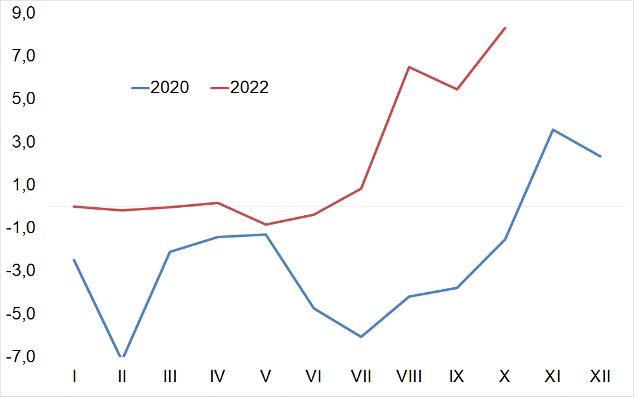

Exchange rate. Inflation might be much higher, but for the balanced NBU management of exchange rate dynamics. As previously indicated, the devaluation of the hryvnia is one of the most significant factors of inflation (together with the housing and utility services). Both in 2020 and 2022, the NBU rationally dosed the "release" of the hryvnia and restrictions (up to an actual ban) on the purchase of foreign currency by the population and businesses (diagram "Purchase rate of cash dollars by the population"). Of course, of the degree of NBU intervention in exchange rates and the impact of such intervention on macroeconomic balances remain debatable. In our opinion, in crisis conditions, the central bank cannot take the position of an observer in relation to exchange rate dynamics.

Consumer price rise, % to the previous month

Cash dollar purchase rate, UAH / $1

2021

2022

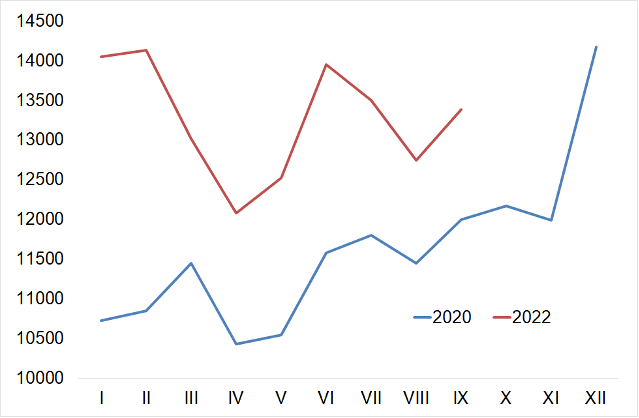

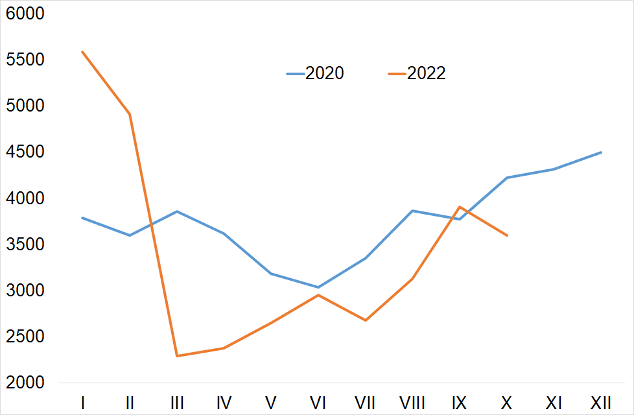

Average wages in Ukraine, UAH

Nominal wages in 2022 are determined through calculation of pensions in the Pension Fund.

Wages. Both the pandemic and the Russian aggression led to loss of jobs, massive unemployment, and a decrease in wages funds (including as a result of production drop). Therefore, the fall of wages in spring was expected (diagram "Average wages in Ukraine"). Although in the 2nd quarter of 2020 wages went up again, their real purchasing power remained limited (due to inflation).

An even more significant decrease in real wages is observed in 2022. A number of production factors (characteristic for both periods) — the growth of prices for energy resources and logistics, a decrease in the marketing activity, including exports — exhausts the resources of enterprises, which (under other conditions) could be spent on wages. Physical destruction of production facilities makes labor remuneration impossible.

Household resources. Although wages stay at the level of the year beginning, household resources show a significant upward trend. Firstly, there was a significant growth of household deposits, which was practically not observed two years ago. During the coronavirus period, deposits grew at an insignificant pace, due to both economic recession and falling demand for everyday goods and services (saving attempts were accompanied with consumption of lower-quality, and therefore cheaper goods), with cash payments.

The main factor of such an increase in deposits in 2022 was presented by payments to the military, which (unlike in previous years) are made on time and in full, thanks to financial support of partner countries to Ukraine (nothing like this was observed earlier).

Secondly, there was a noticeable increase in transfers from abroad as wages for both Ukrainians working abroad and those who remain in Ukraine, working in international companies and representative offices. In the first months of the coronavirus crisis, wages fell significantly, due to the uncertainty of the Europeans, from where the lion's share of transfers comes to Ukraine (diagram "Balance of incomes from wages abroad").

Balance of incomes from wages abroad, $ million

Thirdly, an increase in the monetary resources of households in Ukraine definitely leads to an increase in the purchase of cash foreign currency (diagram "Net sales ...").

Net sales of cash currency to the population, UAH billion

Since the population traditionally views cash dollars as a reliable resource for long-term savings (which creates a significant demand for them), in the conditions of the current risks associated with a possible military escalation, the purchase of cash currency will continue, which will naturally put pressure on the exchange rate, and with that will require currency interventions. However, the financial assistance of international partners, as well as the restoration of foreign trade (primarily, exports) (also thanks to partners) will allow maintaining the appropriate level of reserves.

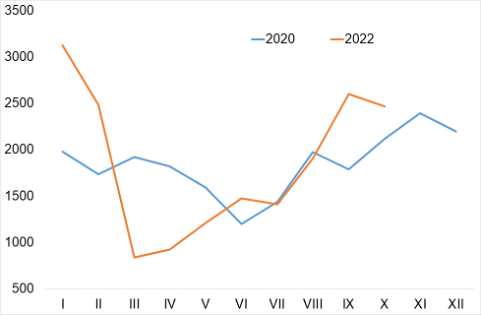

Export of goods. The decline in the exports of goods in the first months of 2022 seemed catastrophic (and correlated with the mentioned GDP drop), but turned out to be short-lived. What is more unexpected is that the volume of exports in 2022 (and to a large extent its structure) are quite close those in the coronavirus year of 2020 (with international trade restrictions) (Chart "Export of goods"). In general, the drop of exports of individual product groups varies depending on pandemic and war losses, as does the "demand" for domestic products exported to foreign markets.

Export of goods, $ million

Exports of agricultural products and foodstuffs was especially successful in 2022 — it decreased by only about 10%, and in recent months almost caught up with 2020 (diagram "Export of some groups...foodstuffs..."). Such a relatively small decrease is due to the fact that the domestic agricultural and food sectors already enjoy a steady demand on international markets, and thanks to the "grain corridor". Therefore, if it stays, we can expect a further "pull-up" of agricultural exports.

The situation with the (previously) second most important group in the export structure — ferrous and non-ferrous metals — is just the opposite. The loss of capacities and assets as a result of the war and bombing of metallurgical enterprises in the South and East of Ukraine led to a collapse of exports (diagram "Export of some groups...ferrous and non-ferrous metals..."). Probably, this export group will not be able to renew its position in the national export structure, at least without significant structural changes and large investments in the latest metallurgical technologies.

Export of some groups of goods, $ mio

Foodstuffs and raw materials for their production

Ferrous and non-ferrous metals and products thereof

Instead of conclusions. Two crises in a row (and who knows when the war will end) is a severe test for the Ukrainian society. At the same time, no one can guarantee that humanity will not face the threat of a new pandemic or environmental crisis soon, which will also be devastating, primarily for emerging countries.

The fact that the Ukrainian economy shows impressive signs of resilience in the face of long-term, large-scale Russian aggression forms positive signals that the lessons of previous crises are and will be taken into account by the authorities during the period of the country's recovery. In that period, the country will face serious risks. While the country demonstrated solidarity to repel aggression against a "real" enemy, this unfortunately does not mean that a strong unity of action will be maintained in the future. The history of Ukraine testifies that the biggest losses of independence and freedom took place in peacetime, when patriotic forces failed to unite, lost the trust of citizens, facilitating the revenge of anti-Ukrainian forces.

Today, there are reasons to expect that peaceful restoration of the country will be successful, including thanks to partner countries. This is what we all hope for.