The Sociological Service of the Razumkov Centre has been monitoring the role and place of religion in Ukraine since 2000. The latest national survey was conducted from 23 to 28 March 2018 with support of Konrad Adenauer Foundation Office in Ukraine.

The study was carried out in all regions of Ukraine, except Crimea and the temporarily occupied territories of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts. 2,016 of Ukrainians aged 18 and over were polled. Theoretical error of the sample does not exceed 2.3%.

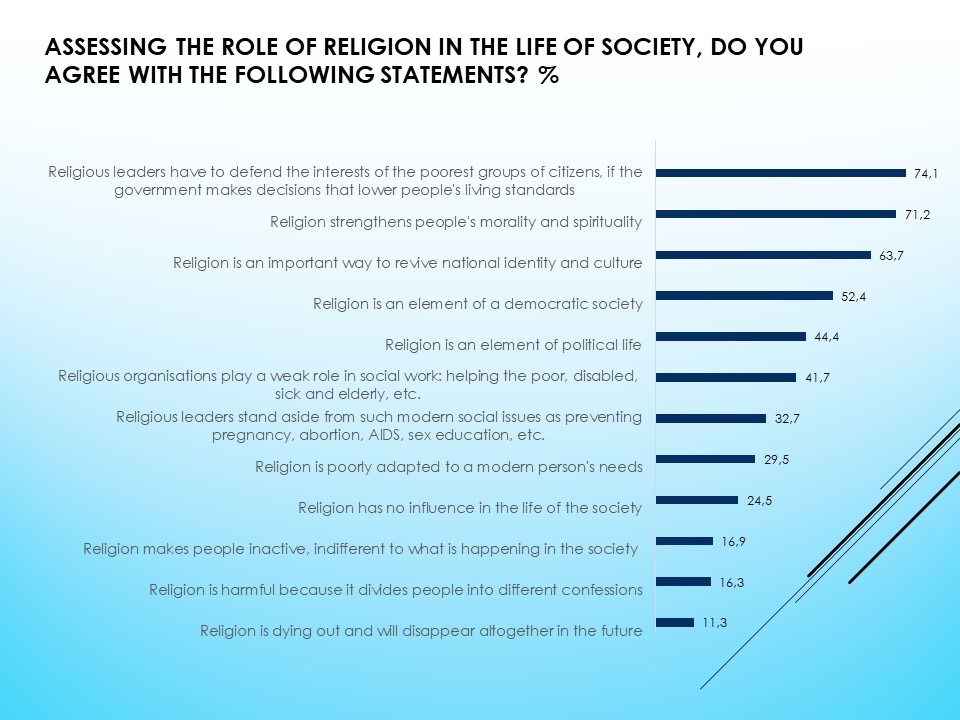

Most citizens recognise the influence of religion on certain aspects of society's life. To some extent, respondents' perception of social life aspects that are influenced by religion reflects their expectations of religion and church. Thus, 71% of citizens believe that the role of religion is to "strengthen people's morality and spirituality" (most often in the West (90%), least often — in the East (58%)); 64% see it as "an important way to revive national identity and culture" (most often in the West of the country (82%), least often — in the East (48%)), 52% — as "an element of a democratic society" (most often in the West (70%), least often — in the East (40%).

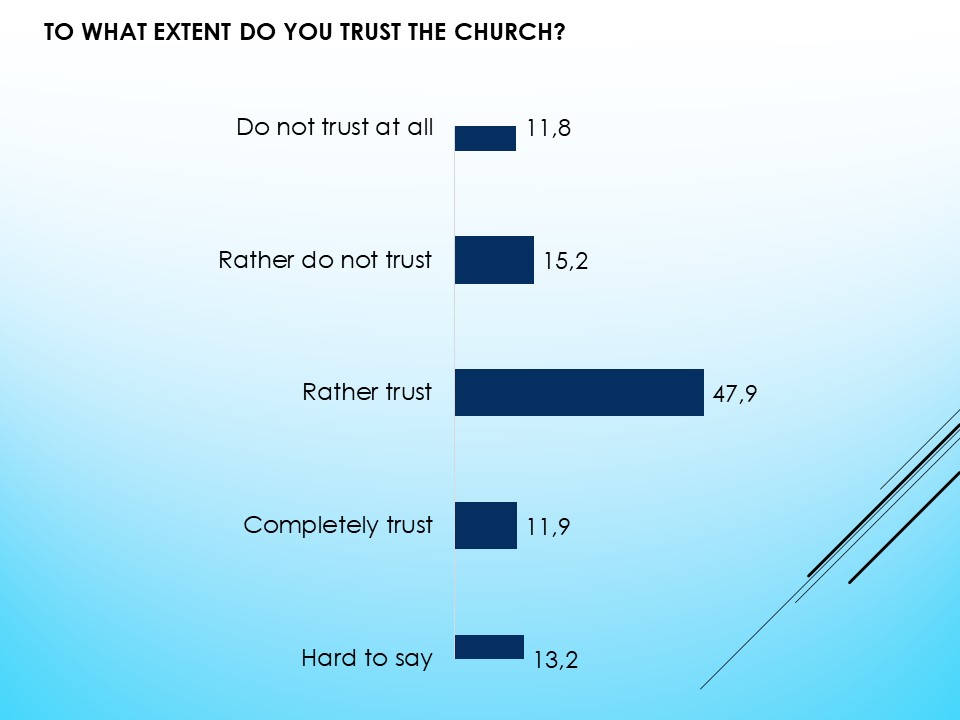

Trusting the Church. Trustwise, the Church retains one of the top positions among social and political institutions (next to volunteer organisations and the Armed Forces). Along with this, compared to 2010, when the level of society's trust in Church was at its peak (73%), now this percentage is smaller (60%). In the regional breakdown, the level of trust correlates to the overall level of religiousness — while in the West, 83% of respondents think that Church is trustworthy (level of religiousness — 91%), in the East — it is only 48% (level of religiousness — 63%). In all regions, the number of those, who think that Church is trustworthy often exceeds those, who do not trust it (however, in the East, a rather large portion of people have no trust in Church − 39%). At the same time, we noted a rather large portion (23%) of those, who could not make a decision regarding this question, in the South of the country.

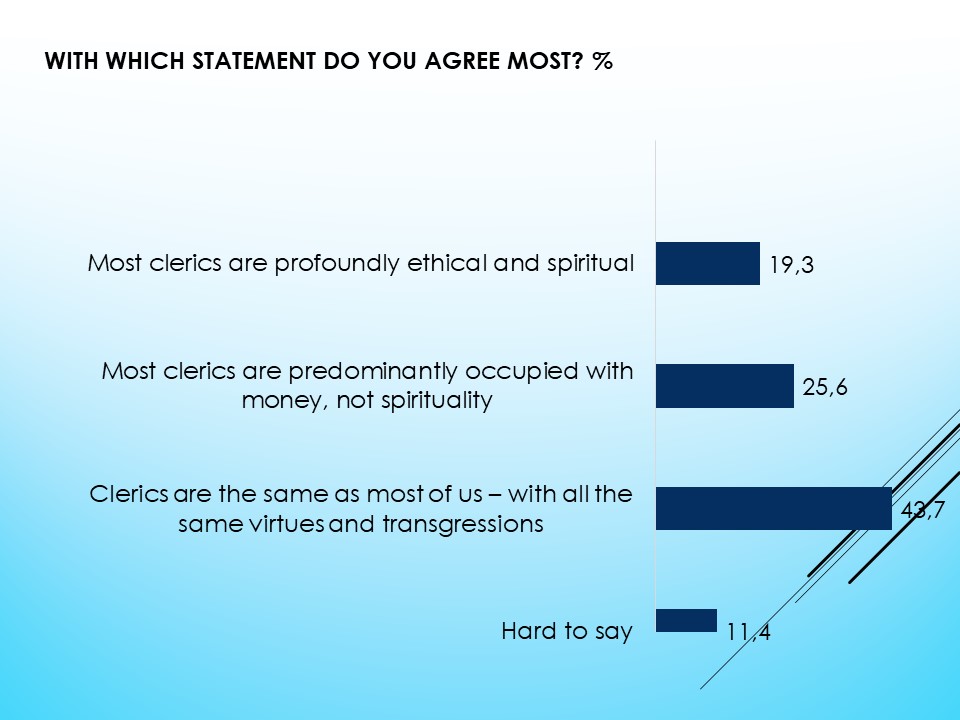

At the same time, the high level of trust in Church is rather a reflection of people's attitude to religion and its potential role in the society, than the reflection of attitude to church representatives. Only 19% of respondents believe that "most clerics are profoundly ethical and spiritual" (and percentage of those, who support this statement has been declining — in 2010, there were 26%). Most citizens believe that "clerics are the same as most of us — with all the same virtues and transgressions". At the moment, 44% of respondents support this statement. 26% believe that "most clerics are predominantly occupied with money, not spirituality" (in 2010, there were 17%).

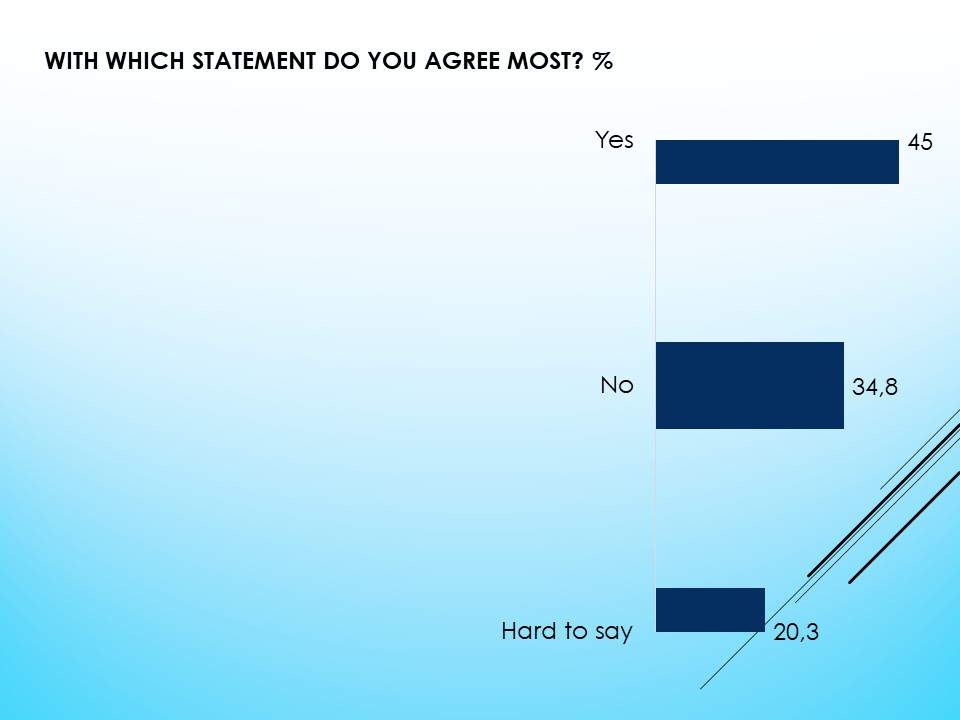

Church as the moral standard. The high level of trust in the Church is in contrast with the percentage of people, who accept it as a moral standard. At the moment, 45% of respondents view the Church as a moral standard, while in 2010, there were 56%). 35% do not see it as a moral standard (vs 27% in 2010).

People's positions on this issue had pronounced regional differences: the Church is a moral standard for 74% of residents in the West, while the percentages in the Centre and the South are much lower (41% and 39%, respectively), and even less in the East (only 28%). Eastern region is the only one, where the majority of respondents (52%) state that the Church does not represent a moral standard for them. In the East, people typically have a low level of trust in representatives of all major churches in Ukraine (including those most represented in this region).

84% of respondents that attended Church on the Sunday before the survey view Church as a moral authority, and only 33% — among those, who did not attend Church that week. Obviously, the very perception of the Church as a moral authority or absence thereof is the cause of people's decision to attend or not to attend Church.

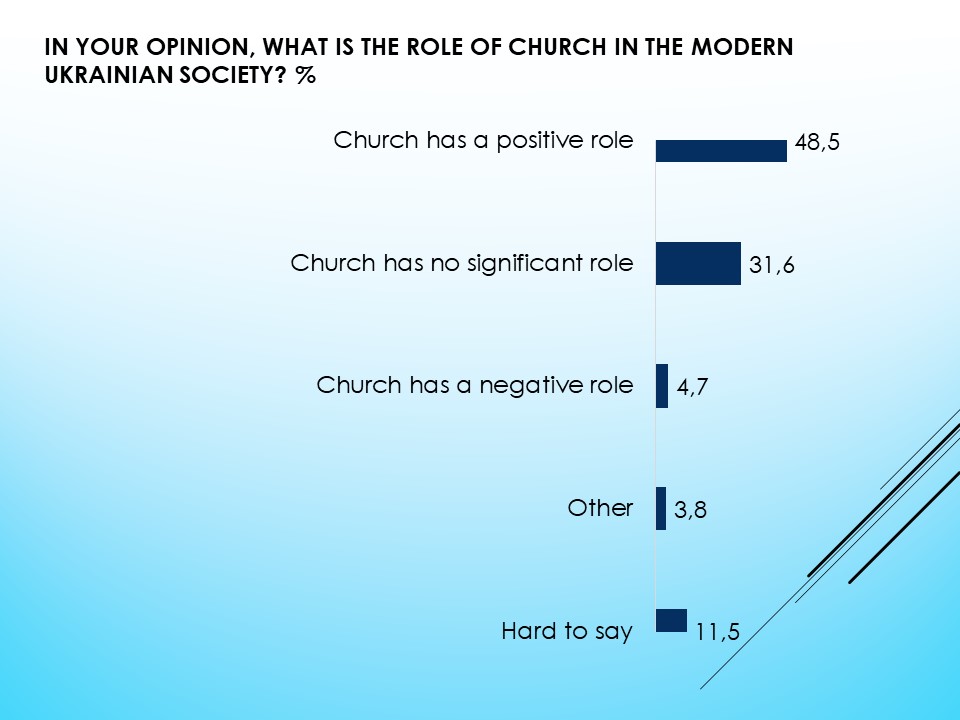

Only 49% of respondents believe that Church has a positive role in the modern Ukrainian society. Again, most often, the role of the Church is described as positive by Western residents (74%), while in the Centre this percentage is 45%, in the South − 43%, and in the East — only 33%.

It is worth noting that we are not talking about the negative role of the Church. Only 5% of respondents view it as that (from 2% in the West to 8% in the East). At the same time, a major group of respondents (32%) say that "Church has no significant role" — here, assessment of people from the Centre, South and East (35%, 37% and 39%, respectively) is drastically different from the point of view of people from the Western region (only 15% support this statement) (diagrams "What is the role of Church…?").

Most often, the positive role of Church is noted by UGCC (Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church — 84%) believers, less so — by UOC KP (Ukrainian Orthodox Church — Kyiv Patriarchate — 63%) and UOC (54%), even less — by "simply Christian" (40%) and "simply Orthodox" (35%), and very seldom — by those, who do not identify as a follower of any religion (5%). The latter had the largest group of those, who believe that the Church has a negative role (21%).

Possibly, the authority of the Church is not so strong, because people think it is not active enough in social life. Thus, most respondents(74%) believe that "religious leaders have to defend the interests of the poorest groups of citizens, if the government makes decisions that lower people's living standards". Residents of the West and Centre agree with this statement more often (82% and 77%, respectively), as compared to citizens in the South and East (69% and 65%, respectively).

At the same time, the relative majority of respondents agree that religious organisations' role in social work is weak: helping the poor, disabled, sick and elderly, etc. (42% of respondents agree with this vs 34% of those who disagree). Yet, it should be noted that the percentage of people agreeing with this statement has decreased compared to 2000, when it was 52%.

The situation differs by the region: while in the West, the relative majority (47%) disagree that religious organisations' role in social work is weak (only 31% support this point of view), in all other regions — the relative majority of respondents support the opinion that religious organisations' role in social work is weak.

Also, the level of trust in the Church is lower among those respondents that view religious organisations' role in social work as weak, as compared to those, who disagree with this (52% and 76%, respectively).

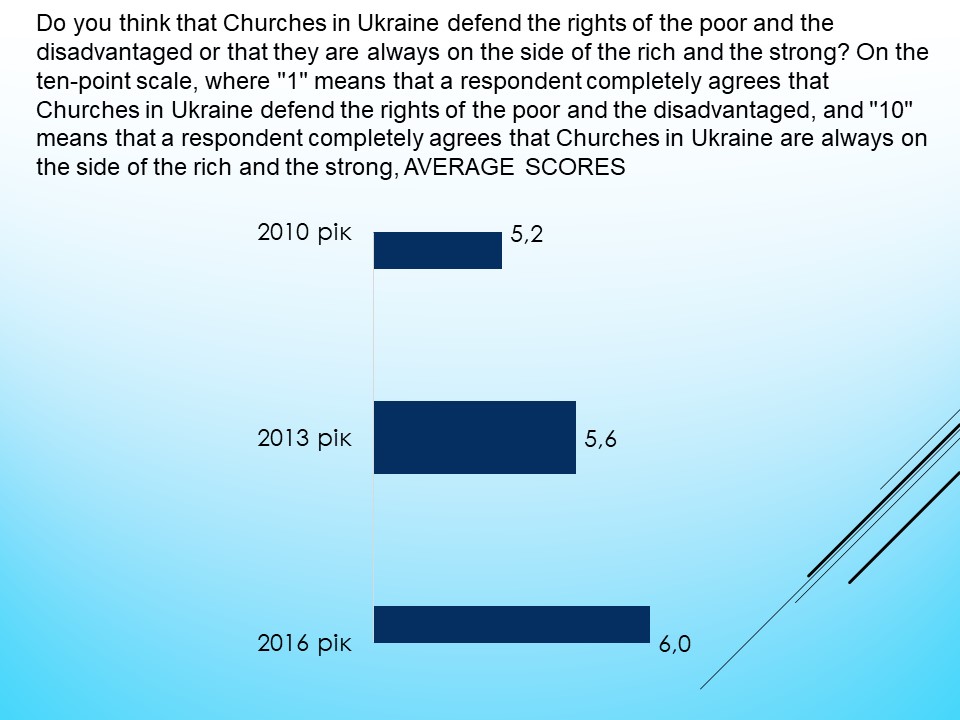

Assessing, on which side the Church stands regarding "the poor and disadvantaged vs the rich and strong", citizens are increasingly more inclined to believe that the Church is leaning somewhat more towards "the rich and strong": while in 2010, on the ten-point scale (where "1" is "defending the rights of the poor and the disadvantaged", and "10" — "the rich and the strong"), Church's position was given 5.2 points, in 2018 this number was 5.9. The only region, where the number was below 5 — was the West (4.9 points); in the rest of regions — from 5.4 points in the South to 6.6 points in the East of the country.

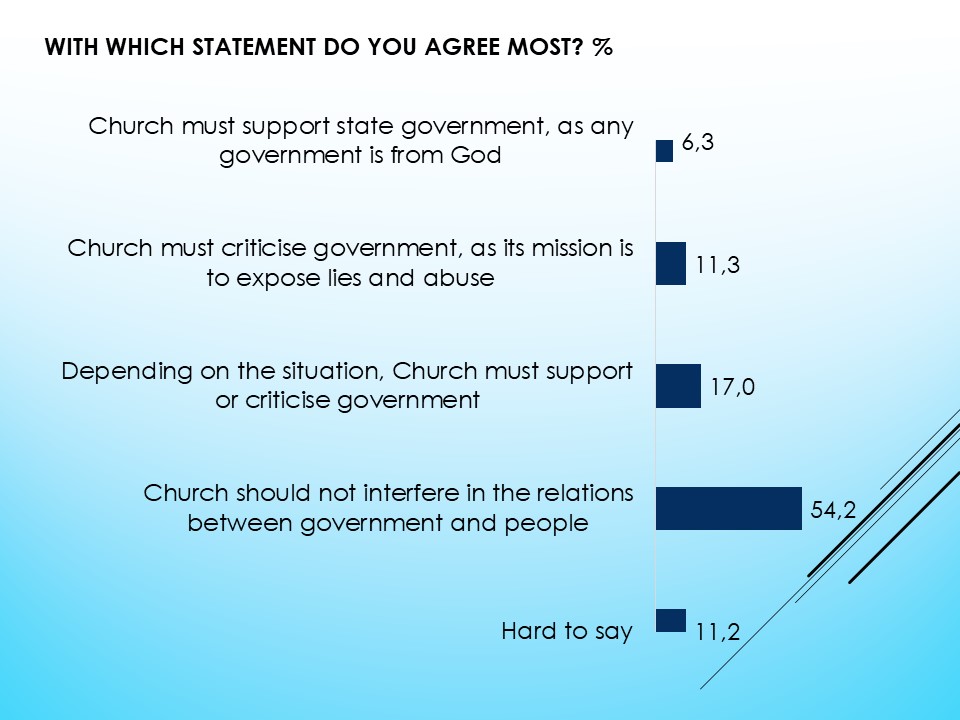

As previously, most people believe that "Church should not interfere in the relations between government and people". Yet, the number of those, who support this statement went down from 63% in 2010 to 54% in 2018. Instead, the number of those, who think that "depending on the situation, Church must support or criticise government", has slightly increased — from 10% to 17%. Another 11% of respondents believe that "Church must criticise government, as its mission is to expose lies and abuse". So, over a quarter (28%) of citizens demonstrate an existing demand for a Church's critical position regarding government. Only 6% chose the statement that "Church must support state government, as any government is from God".

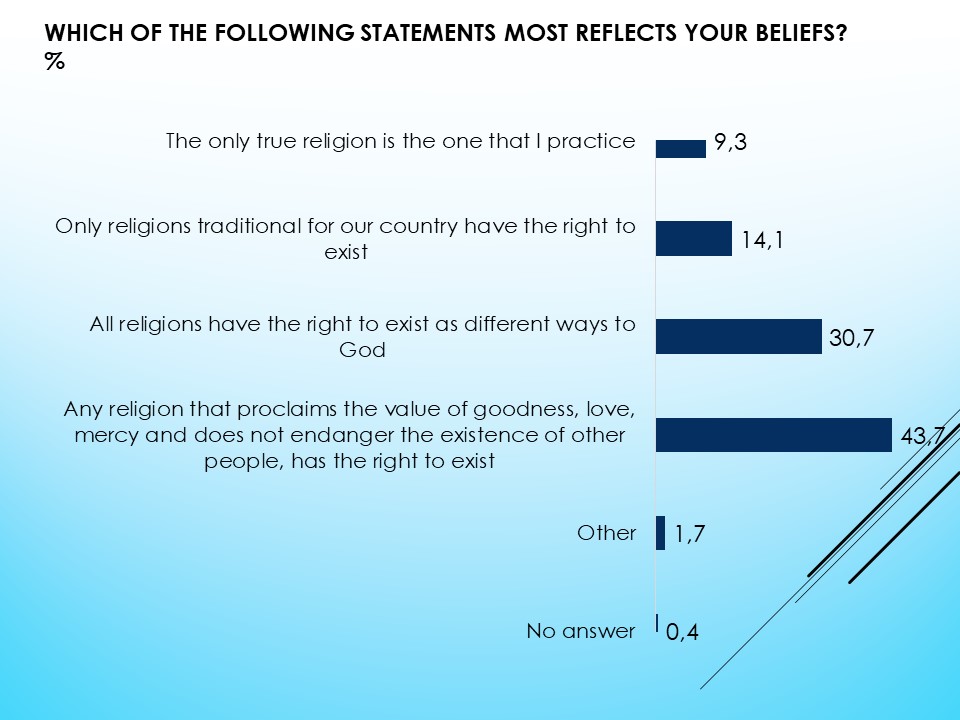

Ukrainian society on the overall remains tolerant to practicing different religions. As previously, the majority of citizens believe that "any religion that proclaims the value of goodness, love, mercy and does not endanger the existence of other people, has the right to exist" (44%) or that "all religions have the right to exist as different ways to God" (31%). Compared to 2017, the general number of those, who chose these two options, did not change much.

Only 9% of respondents supported the opinion that "the only true religion is the one that I practice", another 14% were convinced that "only religions traditional for our country have the right to exist".

There was a certain correlation between respondents' positions and their church/religious self-identification. Representatives of UOC and UGCC were slightly less tolerant to the freedom of religion, than UOC-KP supporters, "simply Orthodox", "simply Christian" and Ukrainian citizens in general. Over a third of UOC and UGCC (38% and 35%, respectively) supporters believe that only the religion they practice or the religions traditional for the country have the right to exist (diagram "Which of the following statements on religion…?").

|

|

Positive |

Indifferent |

Negative |

Did not think about it |

Did not hear anything aboutthis religion (denomination) |

No answer |

|

Orthodoxy |

78.3 |

14.7 |

1.1 |

5.7 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

Greek Catholicism |

41.7 |

38.7 |

3.6 |

15.4 |

0.5 |

0.1 |

|

Roman Catholicism |

36.2 |

41.6 |

4.0 |

17.0 |

1.0 |

0.0 |

|

Protestantism |

19.0 |

44.7 |

12.7 |

20.8 |

2.6 |

0.1 |

|

Islam |

14.1 |

43.5 |

18.6 |

22.3 |

1.4 |

0.1 |

|

Judaism |

13.0 |

45.1 |

13.5 |

25.1 |

2.8 |

0.4 |

|

Evangelical and Charismatic churches |

13.0 |

39.9 |

16.2 |

23.6 |

7.2 |

0.2 |

|

Eastern religions and spiritual practices (Buddhism, Yoga, etc.) |

16.2 |

41.5 |

9.9 |

27.9 |

4.3 |

0.2 |

Citizens are mostly positive or indifferent toward different religions and religious denominations. Most often, people expressed positive attitude to Orthodox religion — 78% (from 82% in the Centre to 74% — in the East). Positive attitude to Greek Catholicism was expressed by 42% of respondents, indifferent — 39%, negative — only 4%. Regarding all other religions and religious denominations, the overall attitude was indifferent, yet, quite noteworthy were the shares of respondents who expressed negative attitude to Islam (19%), Evangelical and Charismatic churches (16%), Judaism (14%), Protestantism (13%).

Attitude to some religions and religious denominations had very pronounced regional differences. Thus, in the West, the overall majority of respondents (74%) noted their positive attitude to Greek Catholicism, while in the other regions of the country, the relative majority of respondents were indifferent to it (from 46% in the Centre to 38% in the South); there was a similar distribution of positions regarding Roman Catholicism: in the West, the majority of respondents (61%) expressed their positive attitude to it, while in the other regions, the relative majority noted their indifferent attitude (from 49% in the Centre to 39% in the South; tables "What is your attitude to the following religions and religious denominations?").

While the relative majority of UOC-KP congregation (48%) expressed their positive attitude to Greek Catholicism, the relative majority of UOC believers (45%) had an indifferent attitude to it. A similar tendency shows in the attitude to Roman Catholicism: the relative majority of UOC-KP congregation (43%) had a positive attitude, and the relative majority of UOC supporters (46%) — indifferent.

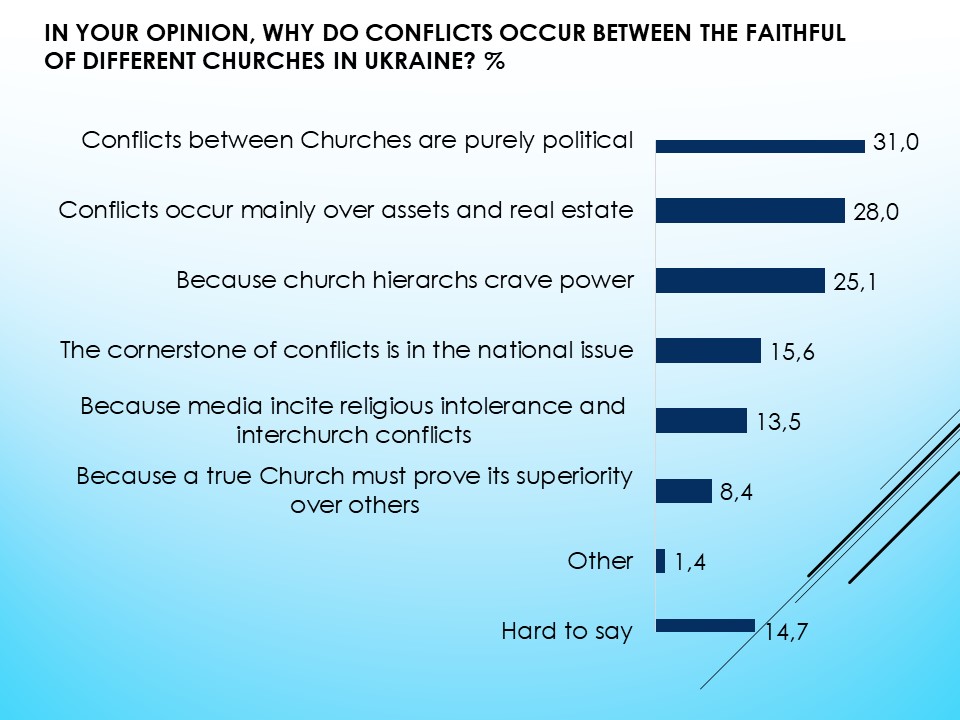

Assessing the reasons for interchurch conflicts, respondents note most often that "conflicts between Churches are purely political" — this is the opinion of 31% of respondents (although this percentage is notably smaller than in 2017, when 37% of respondents thought so); such factor as conflicts over assets and real estate, as well as conflicts caused by church hierarchs craving power, took second and third place (28% and 25%, respectively). The level of support for the statement on hierarchs' ambitions has gone significantly down compared to 2000 (from 39% in 2000 to 25% in 2018), support for the property statement is somewhat higher than in 2000 — 28% vs 23%, respectively, but lower than the 2010 percentage (35%).

Residents of the West cite property factor as the reason for conflicts most often, in the South and East — political factors are named most often, and in the Centre — political and property factors, as well as "power ambitions" of hierarchs are almost equally common.

There is a notable percentage of those, who believe that the reason for interchurch conflicts is "in the national issue": during the monitoring period, it never dropped below 10%, and in 2010, reached 18%. In 2018, this percentage was 16%: from 12% in the Centre to 20% − in the South.

14% of respondents believe that media incite religious intolerance and interchurch conflicts.

So, we can make the following conclusions:

• Religious and church/denominational issues have a distinct regional character. Traditionally, the Western region has the highest level of religiousness, Southern and Eastern — the lowest. Also, in the South and East, people's religious self-identification is unstable, which is a reflection of the general contradictory nature of changes in the collective consciousness of these regions.

Most often, Ukrainian citizens view the role of religion and Church as that of "strengthening people's morality and spirituality", serving as "an important way to revive national identity and culture", "supporting the development of a democratic society".

• Only 49% of respondents believe that Church has a positive role in the modern Ukrainian society. Besides, the level of seeing Church as a moral standard is dropping (this is especially typical for the East).

Possibly, the authority of the Church is not so strong, because people think it is not active enough in social life. Assessing, on which side the Church stands regarding "the poor and disadvantaged vs the rich and strong", citizens are increasingly more inclined to believe that the Church is leaning somewhat more towards "the rich and strong".

• We can assume that Ukraine's Churches can use the idea of serving the society and taking an active social approach as the foundation for finding ways to work together and compromise.