The beginning of 2024 was marked by the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, political passions in the USA, tension in Europe, economic difficulties in China, which noticeably weakened attention to events and processes in other parts of the world, including those lying at the intersection of the interests or influences of the world's leading powers or institutions. However, changes in those regions in 2024 promise to be highly controversial and conflict-prone, fraught with global risks and challenges.

Until now, it was clear to everyone that global events and processes were driven (directly or indirectly) by the US, China and their rivalry. Today, there is an impression that the situation in the world will take on significantly different features, and the year 2024 may turn out to be a year of losses and discord, even in those areas or spheres that seemed well-established and associated with democracy, economic development and human values.

2024 will see elections of the highest bodies of power in many countries, with increased (even provocative) activity of populist, right- and left-wing political parties (including those that are ready to seize power at any cost), and with that — deepening of social and political uncertainty in separate countries (even with stable democratic traditions) and regionally (even globally).

Until now, there was no doubt that the USA, together with the EU, present an influential global force protecting democracy and countering aggressive intentions of authoritarian countries, but now, those centres of democracy may well become sources of global instability. The unprecedented and risky nature of such scenarios is further enhanced by the fact that the authority and influence of international institutions that largely cared about the compliance with the established civilisational rules of the game and at least partially regulated the acceptable (based on a compromise) global order have sharply deteriorated in recent years.

Of course, social and political confrontation will bring an increase in economic troubles, shocks in currency and strategic commodity markets, which, in turn, will add to socio-economic shocks and socio-political tension. It is not yet known how destructive such a spiral of mutual influences can be, but it does not predict anything good.

It should be noted that historically, attempts to change the global order were associated with a reaction to the increase in risks and challenges that are "snowfalling" on countries in the short and medium run. Changes in logistic and production supply chains, food and energy risks that bring inflationary shocks, blackmail of autocratic countries — resource monopolists — these are just some of the areas that are associated with transformations that can shock and change the value system around the world.

Shift of accents and priorities. For 70 years after World War II, the world order was largely shaped by the North American and European countries and global institutions created by them. In that period, Europe recovered and strengthened precisely thanks to the US support. Today, the situation develops so that probably in less than a year, European countries will no longer be able to count on friendly relations with the USA, on its security umbrella (if the former president returns to power, under whose rule Europe for the first time in the post-war period felt "trapped").

It is clear now that the traditional policy of Atlantic solidarity may undergo significant devaluation, leaving the European Union vis-à-vis the growing economic threats from China and militarist aspirations of Russia.

If until today the USA was seen as a defender of democracy, ready to help (even by military means) its partners and allies, hopes for the US assistance may soon turn prove vain. Specifically, if military and financial aid to Ukraine and Taiwan does not arrive on time today, then tomorrow all young democracies will be under threat of foreign invasion by aggressive neighbours.

Along with this, the closest ally of the USA — the European Union — also faces trials. On the one hand, it stays under the US military umbrella, on the other, it declared strategic autonomy, which is extremely vague and misses the proper political tools to achieve its goals, which makes the European Union vulnerable to hybrid encroachments of authoritarian forces. Only the struggle of Ukraine against the Russian aggressor helped Europeans realize the real threats to security and democracy, led to acceleration of transformational processes aimed at protection of the European values. However, a simple question remains open: whether Europeans will find the powers and capabilities to resist the waves of political populism and nihilism, which increasingly overshadows European values.

Currently, the EU has no adequate institutional framework to respond to new protectionist risks of the US, if the latter returns to America first, or the growing threat of Chinese trade expansion, given the controversy of the economic policy in terms of international trade and investment, migration and financial flows.

However, there is also good news: the leading European countries, first of all, Germany, France, Italy, are more and more aware of the new mission of their countries and the entire European Union in shaping the new global agenda. The question is whether they will have the time to convince and unite partners and allies in the urgency of countering military, political and economic threats to all humanity, especially in view of the upcoming elections, which may radically change the political map of the world.

The political and ideological weakening of the US and the EU, of course, has a global impact and can be especially painful for emerging countries and regions that do not have established democratic traditions yet, although they are trying to step up institution-building, including through joint efforts. First of all, we are talking about the Indo-Pacific region, which in recent years has received (and needs) more and more attention due to both high growth rates (which enhanced its geo-economic significance) and growing competition (bordering on confrontation) between major powers (primarily, the US and China) for regional influence.

This not only requires greater EU focus on the region as such but more importantly, the ability to fund security measures in the region, as the US pushes for increased contributions to implement Europe's strategic priorities and offset China's expansion.

It should be noted that until recently, Brussels tried to avoid involvement in Indo-Pacific confrontation (primarily with China) and concentrated on dialogue and cooperation with all partners based on civilised rules, norms and standards adopted by the existing international institutions. This consistency of the EU policy was respected in the world and gave it significant political leverage to achieve its goals, which gave the EU a real competitive advantage.

Current challenges — ruination of production and logistic chains, inflationary pressure of the imbalances in the agricultural and energy markets (largely caused by Russian aggression), technological and digital competition and limitations — bring together the interests of different countries and regions. These long-term risks are supplemented by new ones: the emergence of artificial intelligence and diversification of cyber attacks, which not only creates problems for economic activity but also bears signs of interference in socio-political and democratic processes, human and electoral rights and can undermine the key foundations of democracy and development. Considering the dynamics and technology of the Indo-Pacific region, there are reasons to say that it will create new models and principles of interaction among countries with different political, economic and social systems — not only between the countries of the region as such but also with the West.

However, there is a burden that can complicate mutual understanding between East and West. The countries of the region still well remember the destructive nature of the crisis of 1997–98, which, according to many experts, was actually provoked by mistakes in the implementation of stabilisation programmes in the region, carried out under the auspices of the IMF and other IFIs, which at that time followed the theories and practices ideologically inspired by the United States.

Therefore, one of the main tasks of the EU today, in terms of strengthening its role in the Indo-Pacific, is to establish new partner relations and introduce civilised rules of the game, with the EU's positions strong enough and accepted by many countries and political groups around the world. This is precisely what the EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific, presented in 2021, pursues, with account of the growing geostrategic competition between the US and China, the possible negative consequences of confrontation between the two superpowers, and the EU task to protect civilisational values, which will allow it not to keep out of the dynamics of the Indo-Pacific region.

Next, the focus will be on two aspects of the Indo-Pacific region development: first, the formation of alliances and unions that, despite their initially economic basis, increasingly acquire security features, and in which European countries and institutions are beginning to play an increasingly active role; and second, strengthening the financial system of the region, in particular, reviving the idea of the Asian Monetary Fund (AMF).

Regional agreements of global significance. First of all, we should note that during the past decade, international economic agreements and alliances were made and renewed, which covered ever more countries of the Indo-Pacific region, being one of the consequences of rapid globalisation, including of an economic nature. At the same time, such agreements are the result of increased competition in the region between the US and China, as both superpowers try to influence regional players in their spheres of interest.

Let us note an important feature of such institutional construction. It is widely admitted that the Global South (most of its countries) is openly moving away from the US. It seems that China will take advantage of the situation and draw the emerging countries into its orbit, even those that historically opposed each other (for example, Iran and the Gulf states).

Paradoxically, the situation looks much more complex, in particular, in the countries geographically close to China, primarily those around the South China Sea. The reason is that China is steadily expanding its presence in the adjacent waters and openly demonstrates its interest in many "disputed islands". Say, it recently published an updated territorial map, where its territorial waters are expanded (and marked with a new "ten-dotted line"). Of course, this led to protests of the countries of the region against such expansionist intentions. As a result, a political community rejecting China's intentions was actually formed.

With China increasingly threatening to use force against Taiwan, the US until recently has rightly focused on evading a conflict over the island. However, there is a risk that confrontation or even war may spill over into the wider area of the South China Sea. China aggressively makes claims to the sea, through which more than $3 trillion worth of trade passes annually. The relevant risks will rise significantly, if the US delays support to the partner countries.

Therefore, it turns out that geographically distant countries "gravitate" to China, while geographically close ones do not share "partner" territorial claims and do not support the Chinese hegemony. The tough position of the littoral countries may lead to further aggravation of relations. So, while the Global South is moving away from the US, part of the South lying in the Indo-Pacific is even more concerned about Chinese intentions.

Noteworthy, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, a number of unions and alliances were created, formally regional but actually global, including in terms of geographic presence. The largest of them include:

- the first global one — Asian-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), the only regional union that includes both the USA and China;

- Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP);

- IndoPacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF);

- Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), and others.

In addition, there appeared so-called security-building initiatives in the Indo-Pacific region. The most prominent of them are the US-led Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) with Australia, India and Japan; AUKUS — Australia, Great Britain, USA; I2U2 — India, Israel, the United Arab Emirates and the United States. As we may see even from their membership, all of them are led by the US and have a rather pronounced security component (with the dominance of the US military power). China, on its part, denounced the potential expansion of the West's military role in the Indo-Pacific.

Of course, competition for the spheres of influence in the Indo-Pacific involved, in addition to the US and China, also the "next in importance" states, such as Australia, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, and South Korea, which have their own global ambitions and goals, including with respect to global logistics routes.

In this list, India occupies a special place (it also has elections year this year, but the current prime minister will probably remain in power). The country has strengthened its relations with the key international players and the Global South, actively participating in global initiatives clearly aimed at countering Beijing: primarily QUAD, IPEF, and the recently created India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), presented as an alternative to China's Belt and Road initiative.

However, the engagement of other countries in the region is significantly limited. So far, the US bears the main financial burden of countering threats in the region from China and Russia. However, the increase in military expenditures by other countries (European and Japanese) can only strengthen, not replace, the US troops, which, as in the case of contributions to NATO, may cause dissatisfaction of the United States.

Therefore, the European Union may enhance its influence not so much by its military presence in the region as by consistent initiatives and processes of peaceful development, with an emphasis on common concerns regarding ecology, green and digital transition, global financial resilience, etc. In December 2021, the EU presented the Global Gateway strategic plan, partially as a response to China's Belt and Road initiative, offering an alternative to countries that need infrastructure investments to enhance their digital, transport and energy connectivity.

However, not all European countries agree to subordinate their policy in relations with the Indo-Pacific to the common EU policy. Relevant initiatives were put forward, in particular, by France (the only European country that controls territories in the Pacific Ocean), Germany and the Netherlands, which released their own strategies for the region. Such competition between the EU and its member states cannot be welcomed without reservations.

Meanwhile, France considers itself a resident of the Indo-Pacific region, as seven of its thirteen overseas territories are located in the Pacific or Indian Oceans, and France is the only EU member state with a military presence in the Indo-Pacific region, regularly deploying naval forces there.

Of course, this does not rule out that the EU and its member states intend to create and deepen tools of structural interaction with the Indo-Pacific security mechanisms. QUAD Plus, still in its infancy, is an ideal start for the EU. Since 2020, when three Indo-Pacific countries, namely New Zealand, South Korea and Vietnam, as well as Brazil and Israel, joined the QUAD to coordinate response to the Covid-19 pandemic through regular telephone consultations, the issue of expanding the reach of QUAD has gained momentum. The EU and its member countries, with their close bilateral ties with separate QUAD states and growing engagement with ASEAN, provide an ideal basis for potential accession to the enlarged grouping.

The situation is different with AUKUS, which for now remains a "closed" security alliance. Say, despite the possibility of Japan joining AUKUS (JAUKUS) as an ally, neither Tokyo nor Washington supports AUKUS+ so far.

Such a closed nature in a way contributed to the community of interests of the EU and Japan in the Indo-Pacific, as well as the widest possible involvement of countries (not only from that region) in projects aimed at global development. Such projects include the International Solar Alliance (ISA), whose framework agreement has already been ratified by almost a hundred countries, which, again, is steadily gaining a security dimension. So, regardless of the conflicts with Great Britain over Brexit or AUKUS, cooperation between France and Great Britain in certain areas, such as maritime security or climate action, is quite fruitful and growing in importance, especially considering that both countries are permanent members of the UN Security Council, NATO (founders), and nuclear powers.

At the same time, Japan is intensifying security partnership with Great Britain and Italy. As Japan seeks to rapidly build up its military capabilities amid growing concerns about its geopolitical environment, the country is also looking to expand its international partnerships in the defence industry. In particular, the governments of Great Britain, Japan, and Italy signed an agreement on the official creation of a new generation fighter jet construction program for these countries.

Considerable attention to the Indo-Pacific region can have contradictory consequences for its development. On the one hand, this means that the region will obtain new trade and investment resources. On the other, the diversity of goals, motives and practices of countries and alliances ready to promote and protect their interests in the region may add to the imbalances of national political and economic actors, causing distrust and confrontation, especially taking into account that the Indo-Pacific "traditionally" was in the centre of currency wars, which can easily provoke a "second" Asian crisis. Moreover, confrontation may stem from the idea of the Asian Monetary Fund — AMF, attractive for many Asian countries, as it is also a source of contradictions between the US and China. Although the EU is not too active financially in the region, the creation of a global financial centre where China plays a dominant role requires close attention.

Shift of emphasis in financial leadership in the Indo-Pacific region. The idea of the AMF was revived in March 2023 by the Prime Minister of Malaysia amid growing concern about another strengthening of the US dollar in the region. The US Federal Reserve rate hikes over the past two years reminded analysts of the Asian financial crisis of 1997 (which quickly became global), and the idea of the AMF was supported in the countries of the Global South.

Moreover, the promotion of this idea simultaneously demonstrated changes in its support and practical implementation. Today, the transformation of the international monetary system is most of all favoured by China, whose currency is already claiming global (or at least regional) status. In a certain way, China today is "replacing" Japan in 1997, when the Asian crisis unfolded. Moreover, at that time, the idea of AMF was proposed exactly by Japan (at that time experienced in Asian and global finance), as a response to the regional financial crisis of 1997.

In 1997, the potential creation of the AMF pursued two goals for Japan. It was primarily seen as a mechanism of much-needed support for rapid and efficient stabilisation of Asian economies. At the same time, it was a geopolitical manoeuvre, as Japan sought to strengthen its presence in the international stage, especially in Asia.

Of course, changes in the world economic and financial processes also changed the attitude to such global processes, and today Japan much less "insists" on its leadership. Japan's vision of regional economic leadership has evolved over the decades, and while risks to the global growth and the possibility of a “crisis contagion” effect persist, the creation of the AMF is no longer seen as part of the solution. Instead, Tokyo focuses on promoting a rules-based order, insisting that countries should abide by the established international law regardless of their political system. The question is whether Japan will be able to create new institutes based on prevailing international rules and norms, especially when it comes to meeting individual national or regional economic needs.

Let us look at the peculiarities of the evolvement of the Asian crisis in 1997–1998, which will show us why Asian countries remained dissatisfied with the role of international financial institutions, primarily the IMF, accusing it of weakness (at that time the IMF was strongly influenced by the USA). And when the IMF and the US Treasury rejected the idea of the AMF, a number of East Asian countries became even more confident that the AMF could become a truly regional stabilisation institute, since the IMF was a tool of US influence in the Indo-Pacific.

Asian crisis spiral. It should be noted that crisis complications arise and manifest not only in individual (emerging) countries but also easily spill over to neighbouring or partner states, and even globally. This is best of all seen in the spread of currency shocks (devaluation). Moreover, the fear of being "late" and losing competitiveness pushes countries to further devaluation, provoking the emergence of crisis spirals — a heavy burden on economies. Note that if the potentially vulnerable "sphere" is large enough, there is a high risk of the spiral spreading to the whole world.

The East Asian "tigers" provide a vivid example of such unfolding crisis. The group of the most dynamic countries of the 1980s and early 1990s (if in the 1980s the dynamic was still not stable, by 2007, the average annual growth rate reached 7–10% — see the chart "Economic growth rates in Southeast Asian countries") in 1997–98 faced a devastating currency crisis, and the dynamic of its development was manifested in the mutual "pushing" of currencies to collapse. Undoubtedly, the causes of the crisis lied in the poor financial and banking system, the reform of which lagged behind the requirements of the late 1990s. However, the unwinding of the crisis spiral had "internal" incentives as well.

Economic growth rates in Southeast Asian countries, % compared to the previous year

Emerging countries need to boost exports, therefore, the countries of the region consistently increased the openness of their national economies (diagram "Openness of Southeast Asian economies"), which in "good" times contributed to development, but the risks of troubles multiplied. Since countries could offer raw and agricultural goods on foreign markets, openness was mainly secured at the expense of imports, which worsened the balance of accounts.

Openness of Southeast Asian economies, Export + Import, % of GDP

First of all, we note that the significant deficit of current accounts in the vast majority of countries in the region was maintained for a long time (since the early 1990s), thereby creating the potential for devaluation pressure (table "Balance of the current accounts").

Balance of current accounts, % of GDP

|

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

|

|

Indonesia |

-1.6 |

-3.2 |

-3.4 |

-2.3 |

4.3 |

4.1 |

|

South Korea |

-1.0 |

-1.8 |

-3.4 |

-1.9 |

10.5 |

4.4 |

|

Malaysia |

-6.1 |

-9.7 |

-4.4 |

-5.9 |

13.2 |

15.9 |

|

Thailand |

-5.5 |

-8.0 |

-8.1 |

-2.0 |

12.5 |

9.8 |

|

Philippines |

-4.0 |

-2.3 |

-4.2 |

-4.6 |

2.1 |

-3.4 |

The next feature was that countries pegged their currencies to the US dollar, or to a basket in which the US dollar dominated, which in effect also meant pegging to it.

Such pegging to the US dollar, given the fluctuations of the dollar against the yen and European currencies, also meant fluctuations in both nominal and real exchange rates of the region's currencies against the yen, mark or franc. In 1991–1995, the dollar was falling relative to other major currencies. Therefore, all Southeast Asian currencies devalued quite significantly against the Japanese and European ones. However, since 1995, the dollar began strengthening in relation to other world currencies, and Asian currencies also strengthened rapidly in real terms. This seriously undermined the competitiveness of those countries.

Significant inflows of capital usually allowed financing the growing deficits of current operations, but the real strengthening of currencies in the region already carried a significant factor of future currency problems. Another interesting peculiarity of real price strengthening is that the degree of this strengthening positively correlates with the currency regime in the following way: the more strictly pegged the country's currency was, the greater was the real revaluation of the corresponding currency. Countries such as Korea, whose currency was not strictly pegged, saw devaluation in real terms, while Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and others, with strict pegging, saw significant revaluation of their currencies (in real prices). Therefore, in the spring of 1997 it became clear that the vast majority of currencies in the region were overvalued, and real devaluation looked like a necessary tool for balancing foreign operations. At the same time, the weakness of currencies made them prone to speculations, and the region was "prepared" for a crisis.

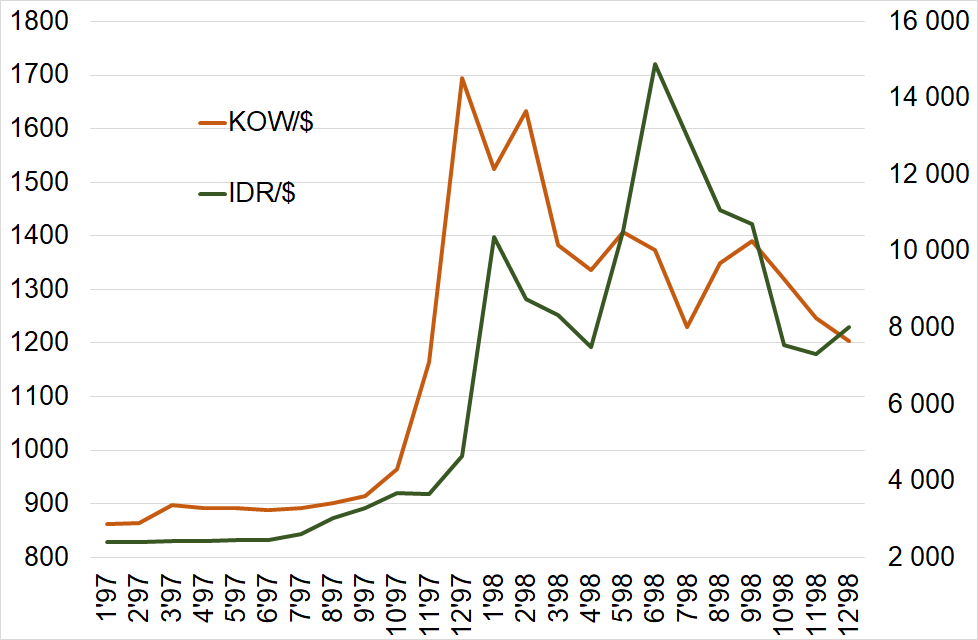

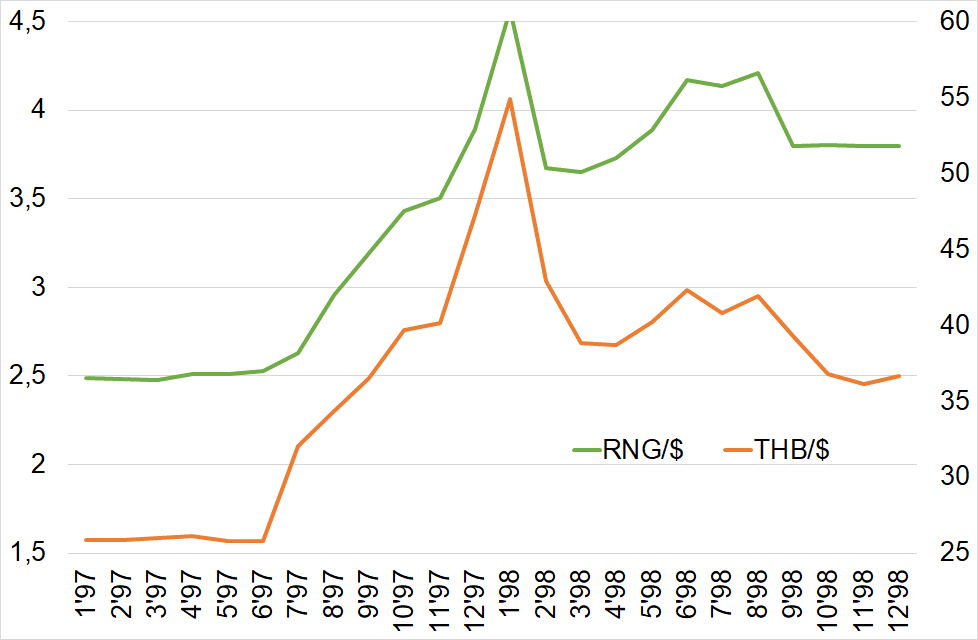

Returning to the crisis itself, note that speculative attacks on the Southeast Asian currencies began in the spring of 1997. The Thai baht, the currency of the country with the poorest macroeconomic indices, was the first to be attacked. As soon as the baht began to devalue, other countries, whose economic conditions and export structure were similar to those of Thailand, also began to lose their reserves and the value of their currencies from August, under the pressure of speculative attacks. Moreover, the currencies seemed to "compete" in falling: depreciation of one of those currencies immediately caused similar devaluation of the rest. By the end of September, compared to the year beginning, the currencies fell in price: the baht — by 42%, the rupiah — by 37%, the ringgit — by 26%, the peso — by 29% (chart "Exchange rates of national currencies to the dollar").

Exchange rates of national currencies to the dollar

|

Korea (left side) and Indonesia (right side) |

Malaysia (left side) and Thailand (right side) |

|

|

|

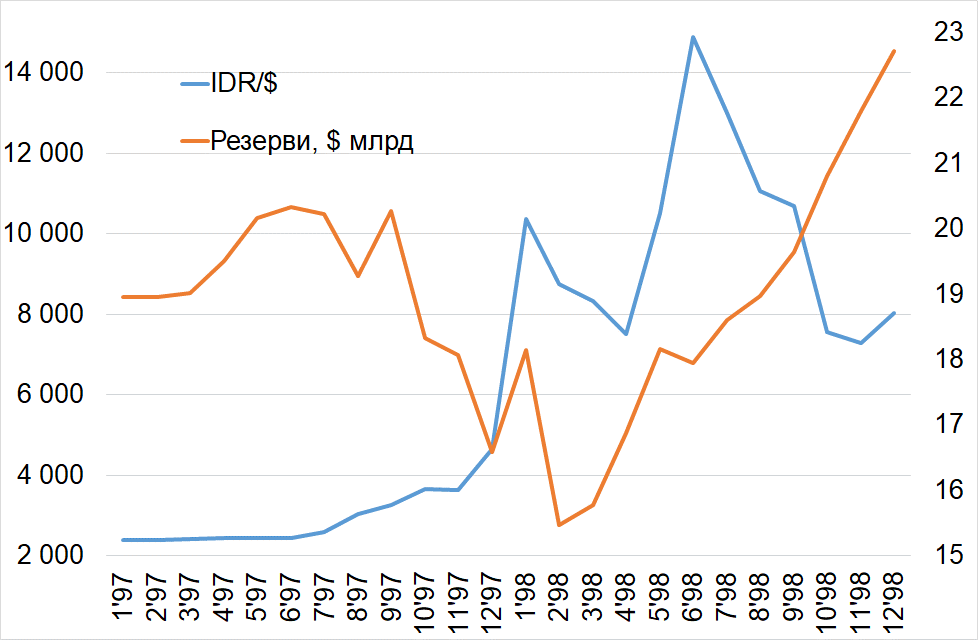

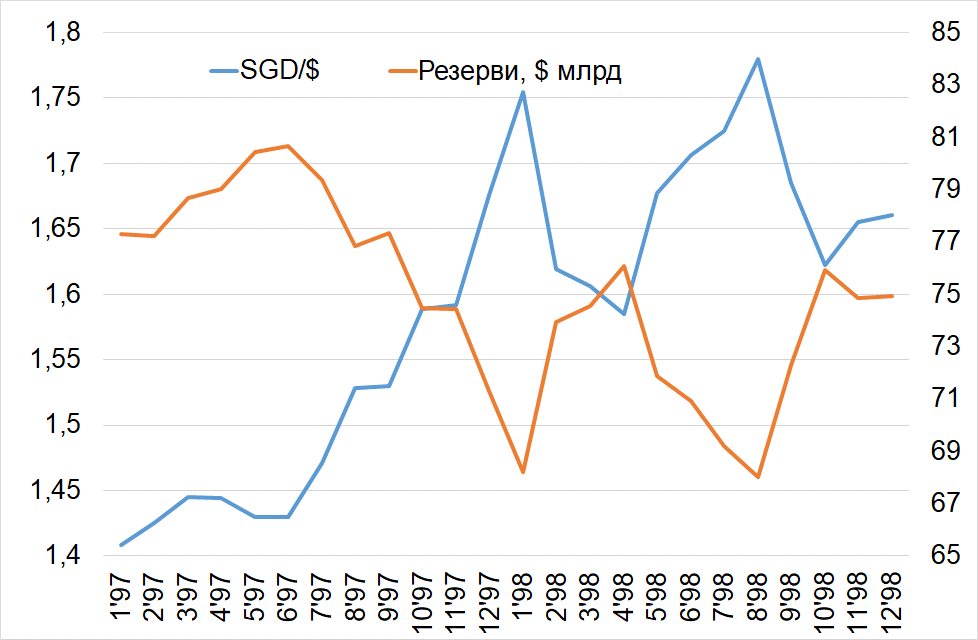

Although Singapore initially came under less pressure (by the end of September, the Singapore dollar fell by only 8%), due to the general decline of the currency of Malaysia (the most important trade partner), its devaluation continued. Hong Kong managed to check the attack, thanks to its Currency Board policy, large reserves and a significant increase in the interest rate. Indonesia, which in January 1998 declared itself unable to service short-term debts, continued to devalue its currency and was covered by another powerful devaluation wave. But by that time, a broad stabilisation plan was already being implemented under the supervision of the IMF (including replenishment of the reserves), and the new pressure did not bring a new devaluation spiral.

Exchange rate to the dollar (left scale) and international reserves (right scale)

|

Indonesia |

Singapore |

|

|

|

Importantly, in 1997, faced with dwindling foreign exchange reserves, Bangkok turned to the IMF for a multibillion-dollar aid package, which was accompanied with strict guidance of the Fund: the banking sector, previously restricted to foreigners was opened to foreign investment, and the baht, the national currency of Thailand, was allowed to float freely. Malaysia, on the contrary, stayed away from the IMF and tried to secure itself from the effects of the global crisis by building barriers to the free movement of capital. The country introduced restrictions on foreign ownership of local banks. In order to stabilise its currency, the government in 1998 pegged the ringgit to the dollar at 3.8 ringgit per dollar and introduced a partial ban on private money transfers abroad.

It should be noted that the development of the crisis, among other things, became possible as a result of the erroneous monetary policy (of both national governments and international financial institutions). The first reaction of the currency regulators was to avoid monetary restrictions and a significant increase in the interest rate. In this way, Thailand, without changing its internal monetary policy, tried to introduce partial control over capital flows, which however had only a minor short-term effect.

Despite the striking difference in the two approaches to economic revival, economic recovery in Thailand and Malaysia took place in the same way: in both countries, foreign exchange reserves increased significantly, the inflation rate remained low, and both currencies stabilised. Such a "synchronous" recovery only raised doubts about the correctness and rationale of the IMF stabilisation policy in the region and worsened the attitude to the USA.

The Asian crisis really had practically global consequences. In fact, it spurred the crisis processes of 1998 in Russia, Brazil, and Argentina. One of the few "islands" of stability remained the European Union, which, of course, actually did not depend on the advice and resources of the IMF.

In addition, the European Union, apart from the development tasks, was preparing for expansion, for which the financial stability of the candidate countries was among the top priorities. The concurrence of the Asian crisis and the launch of the single European currency could provoke serious destabilisation. However, the leader of the European Union, Germany (which was followed by other leading countries of Europe) did not allow significant fluctuations of the mark, and the rates increased only slightly (chart "Mark to dollar exchange rate and rates on the German money markets").

Mark to dollar exchange rate (right scale) and rates on the German money markets (%, left scale)

Moreover, the same policy was simultaneously implemented in the EU candidate countries. The gradual liberalisation of the exchange rate was accompanied with an increase in reserves, which created a "safety bag" for the stability of national economies (chart "Exchange rate of the national currency to the dollar and reserves").

Therefore, European countries, which were already clearly oriented towards European institutions, felt the pressure of the crisis only slightly, which contributed to strengthening the acceptance of the idea of European institutions as a whole.

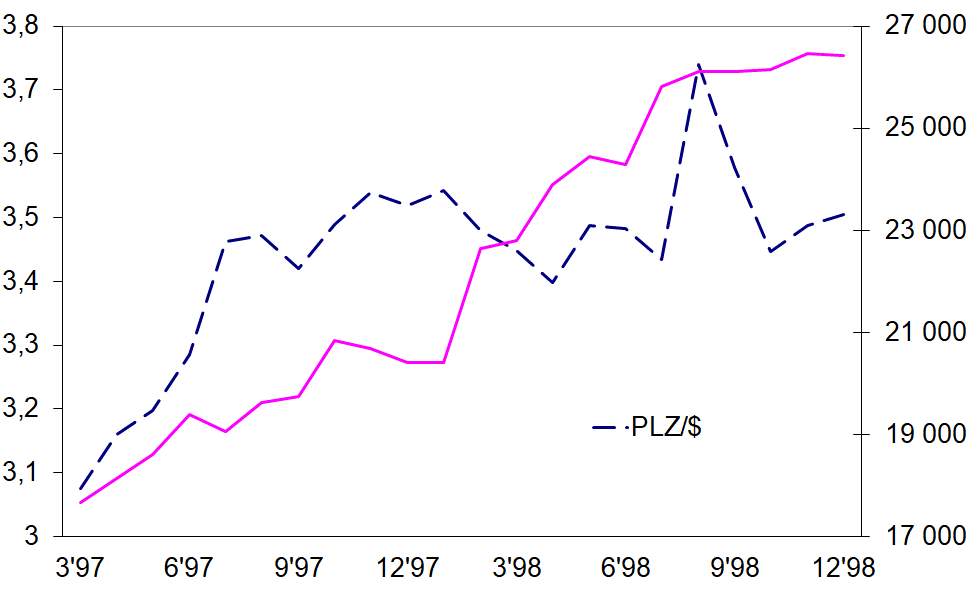

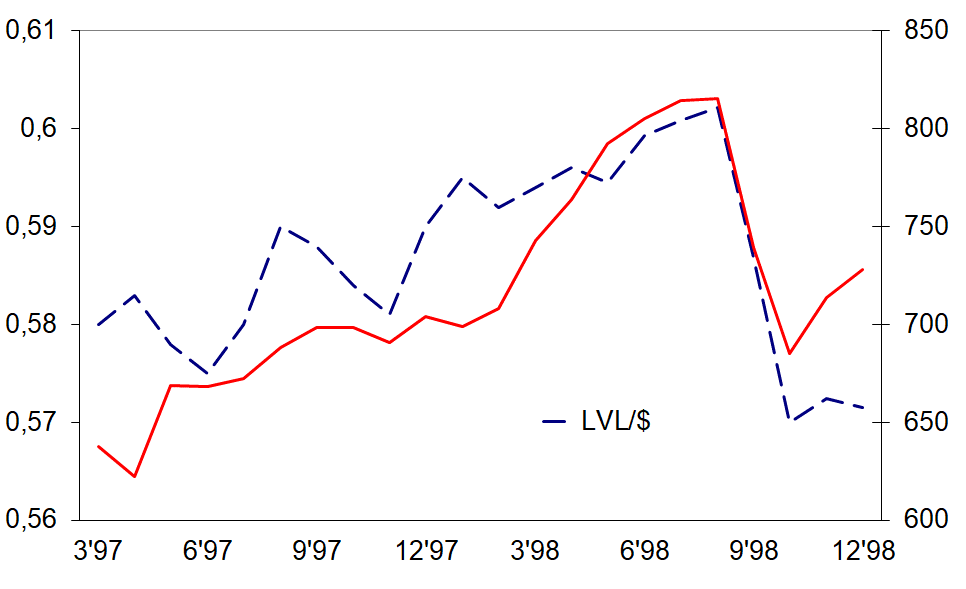

Exchange rate of the national currency to the dollar (left scale) and reserves ($ million, right scale)

|

Poland |

Latvia |

|

|

|

Is the AMF a tool of stability? After the Asian crisis, the idea of AMF was not forgotten. The rate increase by the US Federal Reserve System (followed by most of the leading central banks) from 2022 spurred capital outflows, slowed down economic growth, worsened debt positions — symptoms appeared that had resembled of the panic caused by the Asian financial crisis in 1997. Therefore, the return to the idea of the AMF largely owes to the fear of a possible recurrence of the collapse of 1997–1998.

At the same time, the idea of returning to the AMF turned out to be very attractive for China and its plans to de-dollarize the global finances. Of course, the calls for the creation of the AMF were motivated by the need to prevent a potential economic crisis in the region, not least because a stronger dollar further burdens debt holders in emerging markets.

Note that while the US remains the world's largest economy, as an international financial leader it faces greater competition from China. Moreover, unlike Tokyo (which authored the AMF in 1997), Beijing promotes initiatives that can weaken the US position. One such example was the launch of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2016. To date, the US and Japan remain among the few countries that refused to join this multilateral investment bank. Since then, it has grown into the world's second-largest multilateral development institution, expected to play a key role in bridging the growing infrastructure investment gap around the world.

The creation of a regional financial architecture (with the AMF as the central institution) would reduce the role of the IMF, and thus the US, at least in Asia. However, it is doubtful that this would add stability and predictability to the global financial system.

Why is it important for Ukraine? There is no doubt that 2024 will see re-division of spheres of influence, changes in political and economic partnerships, partner and antagonistic relations among individual countries and alliances.

Such processes will not bypass Ukraine, which heroically resists Russian aggression, thus becoming the eastern outpost defending civilisational values. At the same time, there is an impression that the European Union becomes increasingly aware of its role as a global leader of support for young democracies. This is especially clear against the background of the USA, increasingly preoccupied with domestic politics.

Events in the Indo-Pacific bear features similar to the developments around Ukraine. At first, the EU's role was unclear, against the background of the active involvement of the USA in security processes (active partner support to Ukraine and Taiwan), followed by the weakening of US support to its regional partners (Ukraine, Taiwan, Israel) and uncertainty regarding further assistance.

Instead, the European Union more and more clearly formulates and implements measures and financial steps to support countries that, despite all trials, remain champions of the struggle for democracy and freedom. Even in the face of Russian aggression, Ukraine successfully continues pro-European reforms, passes important European integration laws, and deepens cooperation with Brussels in various areas. Today, the future of Europe depends on Ukraine’s resilience, and there are reasons to hope that this is well understood.

https://razumkov.org.ua/statti/transformatsii-u-indotykhookeanskomu-liderstvi